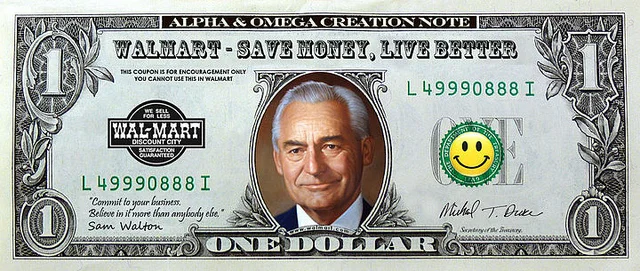

Leadership Journey : Sam Walton

In 1992, at the time of his death, Sam Walton was one of the richest people in the world. But Walton never forgot his humble beginnings. Indeed, those modest origins instilled in him the values that led to his developing one of the most successful retail businesses the world has ever seen: Walmart.

The book, Sam Walton: Made in America is the story of his life and the insights he gained into how you create, run and develop a successful business. We’ll follow him from the origin of his first store all the way to the apotheosis of the Walmart empire, and the novel ideas he introduced to get there.

Growing up during the great depression, Sam Walton learned the value of hard work

Sam Walton was born in 1918, to a lower-class family in Kingfisher, Oklahoma. The Waltons didn’t have much but Sam’s parents made sure he was taken care of. Sam’s father, Thomas, was an honest and hard-working man who took many different jobs in order to provide for his family. Due to his sense of pride, he refused to take on any loans or debt, which meant he was never able to start his own business. Sam Walton understood this, and he would later use a loan to help start his own store.

On the other hand, Sam’s mother, Nan, was quite the entrepreneur, often coming up with ideas to help the family earn extra money. During the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Nan started a small milk business: Sam would milk the cows, his mother would bottle it and Sam would go out and deliver the milk to neighborhood customers. These childhood experiences made Sam Walton realize at an early age that he would have to work hard to earn his keep.

Inspired by his mother’s efforts to bring in money for the family, Walton got his first job when he was just eight years old. He started by selling magazine subscriptions around the neighborhood, and by 7th grade he was out on his bike delivering newspapers.

He continued to earn money as he worked his way toward becoming a college graduate. Walton even hired assistants, expanding his paper route into a small business that made around $5,000 a year.

All of these experiences taught the young Sam Walton an important lesson: hard work pays off. So, by the time Walton was 27 years old and preparing to start his first business venture, he already knew that in order to be successful and get ahead in the world, one had to be willing to put in the effort.

Part of Walton’s success was a result of blatantly copying the good ideas of others.

In 1945, at the age of 27, Sam Walton opened his first discount store, Walton’s 5-10. The store did all right, but Walton knew he could do better.

Walton paid close attention to his competition, and started experimenting with the sales tactics he observed others employing. This led to great success. Indeed, some of these ideas were so good that many of them are still considered standard practice today.

For example, in the 1940s it was normal for discount stores to have multiple cashiers located at different areas. But, while visiting a store in Minnesota, Walton noticed it had only two dedicated checkout counters, each located at the front. He liked this radical idea and put it to use in his own shop, quickly saving money by reducing the number of cashiers.

And after observing a competitor who used wooden shelves to display certain goods, Walton realized this could save money as well. However, Walton took it one step further: he replaced all of his wooden shelves with metal ones. While the new shelves didn’t look as nice, the cheaper cost allowed Walton to keep his prices lower than his competitors’.

Even after he found success, Walton never stopped copying good business ideas whenever he saw them. When he visited a supplier in 1975, Walton noticed how the staff would get together before the day began and perform a company cheer. Walton could see how this activity visibly boosted worker morale. So, upon his return to the States, he implemented his own “Walmart cheer” at the flagship store in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Walmart employees even performed the cheer for President George H. W. Bush when he visited one of their stores. Walton could proudly tell from the look on the president’s face that he had never before seen such enthusiasm from a group of staff.

Walton always put the customer first, but not without controversy.

Sam Walton learned early on that, in order to get ahead of his competition, he needed to spend money to attract customers. After opening his first Walton’s 5-10, he even went so far as to take out a $1,800 loan for an ice cream machine for his customers to enjoy. But he didn’t stop there.

Walton was always on the lookout for ways to draw customers in. When he opened his first store, he would watch as farm families drove into town on Saturdays to shop in the many different specialty stores in order to purchase all the goods they needed. These shops often closed early and held a small selection of goods. This is when the great idea dawned on him: he would keep his store open longer and offer a wider selection of goods for his customers.

This philosophy continued throughout his career. When Walton opened his 18th Walmart in 1969, its low prices, long opening hours and free parking were all reasons customers continued to be drawn to it.

Despite this appeal, Walton took a lot of flack over the years for practices that many people viewed as harmful to small business. But, as Walton saw it, it wasn’t his fault that local competition is put out of business when a Walmart comes to town. After all, the customers are free to choose where to shop, and if they choose Walmart, it must be because they feel their needs are better met there than at local stores.

In fact, Walton believed that his customer-first philosophy has helped local businesses.For example, in Wheat Ridge, Colorado, the owner of a local paint store came into a recently opened Walmart to thank the store’s manager. It turned out that the Walmart paint department had been recommending her store to customers who couldn’t find what they needed at Walmart.

To Walton, this example shows that Walmart cares for its clients so much that they’re willing to sacrifice potential business to make sure customers are satisfied. This is the customer-centric approach Walton would continue to take throughout his career.

Other big retailers didn’t scare Walton; he recognized that competition only made Walmart stronger.

Sam Walton’s business philosophy raises the question: Why avoid competition when you can thrive on it instead? Indeed, observing the competition is what enabled Walton to come up with innovative sales strategies.

Take the area of promotional strategies, for example. In the early 1970s, Walmart opened a new store in direct competition with a town’s Kmart. At this time, Kmart operated around 1,500 stores and Walmart only had 150, so Walton knew they’d need a brilliant idea in order to attract customers.

So, the store manager, Phil, decided to build a huge promotional display featuring a one-dollar-off sale on Tide laundry detergent. To pull this off, however, Phil needed to order a ridiculous amount of the product: 3,500 cases, which, when displayed together, measured 12 by 100 feet!

When Walton got wind of this, he thought Phil had lost his mind! Considering the potential benefit, though, Walton came around and ultimately embraced the idea. And it worked! The innovative promotion grabbed people’s attention and turned out to be a huge success.

Walton admitted that without Kmart to compete with, they wouldn’t have thought to stage such a huge promotion. And these strategies are still part of their business practice to this day. This kind of competition also benefits the customers.

In 1977, a Walmart in Little Rock, Arkansas, began to face fierce competition from a nearby Kmart that had just opened. The Kmart was cutting prices so drastically that Walton was forced to take action; he told the manager to make sure that everything in their store was as cheap as, if not cheaper than, the items in Kmart. At the height of this showdown, the price of toothpaste reached an extreme low of six cents! But Walton didn’t flinch, and eventually Kmart backed off and gave up trying to beat Walmart’s prices.

This experience taught Walton an important lesson: upon the arrival of a big competitor, Walmart prices had to be as low as possible so that customers would remain satisfied.

Although it took time, Walton eventually began to value his employees, turning them into associates.

Sam Walton always recognized the value of his customers. But this wasn’t always the case with his employees. For a long time, Walton was very tight-fisted, a result of his humble upbringing. Unfortunately, this meant that he didn’t always pay his employees as much as they deserved.

In 1955, for instance, Walton received a call from Charlie Baum, a store manager, who informed him that he’d raised his clerks pay from 50 to 75 cents per hour. Even back then, these were pretty pitiful wages, but Walton admits that this didn’t get in the way of his stinginess: Walton told Charlie to revoke the raises, since his store hadn’t yet hit Walton’s goal of a six-percent profit margin.

But Walton changed his ways after a visit to England in 1971.

Walton reconsidered his relationship to Walmart’s non-managerial staff when he came across a sign for an English store that listed the name of the company as Lewis Company, J. M. Lewis Partnership. And underneath the sign was a list of all the “associates” that worked there. This got Walton thinking about his own company. Wouldn’t it be great if Walmart could work in “partnership” with its “associates” instead of simply managing its employees?

Walton quickly set his idea into action: once he returned from the trip, he announced that employees would now be called associates. But Walton also knew that actions speak louder than words. So he started a profit-sharing plan for the new associates that included stock options or cash bonuses, allowing everyone to benefit from Walmart’s success.

Walton knew how to celebrate his successes and learn from his failures.

Sam Walton never slowed during his career. When success arrived, he would celebrate it, using the momentum to keep moving forward. But he admits that he also made some mistakes along the way.

One of his biggest mistakes almost cost him his company. In 1974, Walmart was performing well, and Walton decided he might be able to enjoy an early retirement. So, Walton promoted one of his two executive vice presidents, Ron Mayer, to CEO. But this move ended up causing a lot of bad blood between him and Ferold Arend, the other vice president. As a result, the company split into two groups, one favoring Mayer, and the other one Arend.

Trouble was brewing, so, in 1976, Walton met with Mayer to admit that his early retirement was a mistake and to ask for his old job back.

What happened then became known as the Saturday Massacre: Mayer, and dozens of other senior managers who supported him, left the company, and Walmart’s stock prices fell so low that Walton was unsure if he’d be able to salvage the company.

However, even in the face of this disaster, Walton carried on: he immediately found new managers to fill the empty positions and persuaded an old friend, David Glass, to replace Mayer. Glass proved to be immensely talented and turned the whole disaster around. Under his leadership, Walmart exceeded everyone’s expectations, and sales performance increased almost immediately.

Then, eight years later, Walton celebrated an event he never dreamed would happen. In 1984, Walmart reached a financial milestone: An eight-percent pre-tax profit.

Walton had even made a bet with Glass that this would never happen. When Walton lost the bet, he was made by Glass to step out onto Wall Street dressed in a Hawaiian outfit, where he performed a hula dance accompanied by ukulele players.

Naturally, the press was amazed that one of the most successful CEOs would do something so silly. But Walton says it’s all part of the Walmart philosophy: knowing when to work, and knowing when to celebrate.

Walton also recognized the importance of giving back to the community.

As we’ve seen, Sam Walton had his fair share of critics. But when it comes to a lack of charitable donations, he believed the critics were misguided.

Walton was a firm believer in the power of education and he donated time and money to the cause. He recognized that the future workers of America must have the best education possible in order to succeed. Only thus equipped would they have the skills necessary to keep companies competitive in a rapidly changing marketplace. As of 1992, the Walton family had awarded around 70 university scholarships per year to children of Walmart associates.

But Walton’s philanthropy extended beyond the borders of the United States as well. In the early 1990s, he sponsored 180 Central American children with scholarships to American universities. He hoped that by following through on their education, they’d one day be able to return home with the knowledge to help solve the economic issues their countries were facing. Walton also hoped that with this assistance he could make sure there would be good people on hand to manage future Walmarts in Central American countries such as Honduras or Nicaragua.

Walton also suggested that Walmart’s very existence is itself a form of charity. He pointed to Walmart’s customer-centric approach as being hugely beneficial for the communities it serves. He suggested that, by keeping prices extremely low, Walmart helps communities save billions of dollars every year.

The numbers tell the story: between 1982 and 1992, Walmart sold approximately $130 billion worth of products. And if his store saved customers an average of ten percent on prices, which is a conservative figure, this would mean that during that 10-year period, customers saved over $13 billion.

These savings could therefore help Walmart’s customers improve their living standards, especially those in rural districts who would otherwise have to depend on more expensive small town merchants.

Sam Walton was able to grow his small town variety store into a global retail empire. He made this happen by learning how to put the customer’s needs first, even if it meant sending them to a different store. He also knew that instead of being afraid of competition, a successful business uses it to help their business grow. And, as his business grew, Walton didn’t forget to care for his employees; he recognized them as his “associates” and treated them as such.